TE ĀKITAI WAIOHUA HISTORY

The people of Te Ākitai Waiohua are descended from the eponymous ancestor, Kiwi Tamaki. Te Ākitai Waiohua claim direct descent from Waiohua through the male rangatira line, not by marriage or other relationship.

Huakaiwaka, the progenitor and paramount chief of Waiohua, had a son Te Ikamaupoho who begat Kiwi Tamaki, the progenitor and paramount chief of Te Ākitai Waiohua. Kiwi Tamaki begat a son Rangimatoru, who begat a son Pepene Te Tihi, who begat a son Ihaka Takaanini. The majority of the registered members of Te Ākitai Waiohua today are descended from Ihaka's son, Te Wirihana.

Hua-Kai-Waka

Eponymous Ancestor of Waiohua

\/

Te Ikamaupoho

\/

Kiwi Tamaki

Eponymous Ancestor of Te Ākitai

\/

Rangimatoru

\/

Pepene Te Tihi

\/

Ihaka Wirihana Takaanini

\/

Te Wirihana

The origins and association of Waiohua with Tamaki Makaurau date back many generations through Nga Oho, Nga Iwi and Nga Riki. Te Ākitai Waiohua emerged out of these kinship groups through the eponymous tupuna Huakaiwaka who, as 'the eater of canoes', was responsible for unifying several tribes into Waiohua. The territory of Hua covered all of Tamaki in the 17th Century which continued through to the time of Kiwi Tamaki in the 18th Century with pa sites and settlements throughout the isthmus.

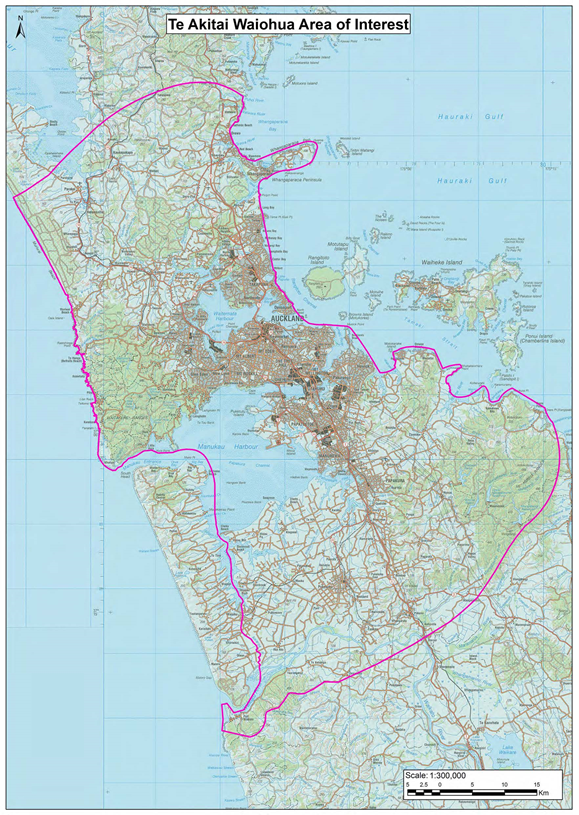

The historical interests of Te Ākitai Waiohua extend from South Kaipara in the North West across to Puhoi and Wenderholm Park in the North East and follows the coast down to Tapapakanga Regional Park and the Hunua Ranges in the South East. The boundary continues from the Hunuas across Mangatawhiri, Mercer, Onewhero and Port Waikato in the South West before moving North to Pukekohe and Patumahoe while excluding Awhitu and Waiuku. The boundary continues North along the coast, including the islands of the Manukau Harbour, past the Waitakere Ranges in the West of Auckland and back up to South Kaipara.

Historically, land in the traditional rohe of Te Ākitai Waiohua has been used for fishing, travel, occupation and cultivation. Settlement was seasonal as the people stayed at main sites during winter, moved to smaller camps to plant gardens during spring, fished and collected kaimoana from fishing camps during summer and then returned to the main settlements again during autumn to harvest and store crops in preparation for winter. Te Ākitai Waiohua were accomplished fishermen and farmers growing fruit, vegetables and raising livestock through to the 1860’s. However, the Land Wars changed everything.

Te Ākitai Waiohua has a strong history with Waikato because of Chief Pootatau Te Wherowhero, who escorted our people from Waikato back to Tamaki Makaurau to resettle the land and offer protection against rival tribes in the early 19th Century. Chief Pootatau Te Wherowhero became the first Maori King in 1857-1858 and Te Ākitai Waiohua readily pledged its allegiance to Kiingitanga (the Maori King movement).

The Land Wars were a colonial response to the Kiingitanga movement, which united various Maori tribes in the central North Island, including Te Ākitai Waiohua, under a central monarch (similar to the Queen of the British empire) as a way of ending land alienation. Kiingitanga was seen by the colonial government as a direct threat to British authority as well as colonial aspirations for land acquisition and settlement in the Waikato. Rising tensions between local Maori and settlers along with rumours of an imminent attack on Auckland by Kingite tribes were sufficient to justify military action. The armed forces of the colonial government invaded the Waikato in 1863 by order of Governor George Grey. The war ended with large scale loss of life and the mass confiscation of 1.2 million acres of land from South Auckland through to the Waikato.

These acts formed the basis of the Waikato Raupatu Claims Treaty settlement of 1995 and the Kiingitanga movement which continues today.

Before the invasion of the Waikato, two Te Ākitai Waiohua rangatira Ihaka Takaanini and Mohi Te Ahi a Te Ngu were stripped of their Crown appointed roles as land assessors due to unsubstantiated reports that they were inciting Maori to rebel against the people of Auckland. Although they protested and challenged the rumours, both were dismissed without further investigation by the Crown.

The situation escalated in 1863 when an ultimatum was delivered by Governor George Grey to those tribes in Manukau that followed the Kiingitanga movement - swear allegiance to Queen Victoria or move off their lands. Ihaka Takaanini was sick at the time and remained in Kirikiri, Manukau with several other women, children and elderly tribal members. This group included Ihaka's wife Riria, their three children and his father Pepene Te Tihi. Mohi Te Ahi a Te Ngu and other members of Te Ākitai Waiohua went into Waikato to support the Maori King.

Pūkaki, Mangere, Ihumatao and its surrounding areas were looted and razed to the ground. Any waka found around the Manukau harbour was smashed or burned. Ultimately various tracts of land in the Manukau region were confiscated (raupatu) under statute by the Crown in 1864.

While in Kirikiri, Ihaka and the 22 other people in his company were arrested by colonial military forces without warrant and incarcerated without charge. They showed no resistance and in July 1863 were marched to the military camp at Otahuhu.

Ihaka's father Pepene Te Tihi and two of Ihaka’s children died while being held at the camp. Ihaka and the survivors were eventually exiled to Rakino Island in the Hauraki Gulf, where Ihaka would also die in 1864.

Riria and the one remaining son who survived the incarceration, Te Wirihana, were left to pick up the remnants of Te Ākitai Waiohua. This is why the vast majority of tribal members today are descended from the surviving son Te Wirihana Takaanini.

A small portion of land confiscated at Pukaki after the Land Wars was awarded back to several Maori individuals after 1864. Some of these persons did not have close familial ties to Te Ākitai Waiohua nor had they lived at Pukaki. These people promptly sold their land interests outside of the tribe. After they were released from Rakino Island, Riria, the wife of Ihaka and mother of Te Wirihana, retained the land awarded to her and her children, providing an opportunity for Te Ākitai Waiohua to rebuild at Pukaki.

With such a limited economic base to start with in a growing urban environment like Auckland, Maori poverty became a real issue with socio-economic consequences such as poor health, education and housing. Te Ākitai Waiohua had already lost most of their land by the 20th Century. Once having pa and kainga sites that were actively cultivated throughout Manukau before the Land Wars in Mangere, Ihumatao, Papakura, Drury, Red Hill, Kirikiri, Ramarama, Karaka, Pokeno and Pukekohe, the land at Pukaki was all that Te Ākitai Waiohua had left.

A new marae at Pukaki was eventually constructed in the 1890’s and the people re-populated the area. Although this new settlement was smaller than previous kainga in the region, over the next 50 to 60 years Pukaki slowly became a sizeable community again. The Wai 8 Report of the Waitangi Tribunal on the Manukau Claim 1985, describes up to 200 families living at Pukaki by the 1950's and the marae dining hall (wharekai) that could seat up to 1,000 people in one sitting. Unfortunately, the constant growth of Auckland as a city necessitated urban development that had and continues to have a significant impact on Te Ākitai Waiohua in the Mangere, Pukaki and Ihumatao region.

The joint development of Auckland International Airport by the Crown and local government during the 1950's and 1960's created zoning restrictions and runway requirements that crippled the ability of Te Ākitai Waiohua to maintain their marae and properties at Pukaki. Most lost their lands due to ratings problems and through sales, causing Te Ākitai Waiohua to effectively abandon Pukaki 'in despair' to live elsewhere, as the marae and local housing fell into disrepair with no means of preserving them.

A three acre block of land was set aside at Pukaki as a Māori Reservation to ensure the people of Te Ākitai Waiohua would at least have a marae on land that was inalienable. The Māori Land Court failed to gazette the land block as a reservation - twice - and the land intended for a marae was accidentally sold into private ownership. With little to return to, the Te Ākitai Waiohua community at Pukaki was disbanded, thereby preventing any initial efforts to rebuild itself.

Today the only pieces of land within tribal ownership include the area upon which modern Pukaki Marae sits, the Pukaki Crater floor and the urupā that sits adjacent to the crater, all of which have been gifted by other parties.

The land beneath Pukaki Marae was gifted back to Te Ākitai Waiohua by the Turner family of Turners and Growers Ltd who were persuaded by their cousin Chief Judge Arnold Turner of the Planning Tribunal. Judge Turner by chance had presided over an environmental case where he heard how the land reserved for a marae at Pukaki had been lost.

The Pukaki Crater floor and Pukaki Urupā near the crater were gifted back by the former Manukau City Council in response to the Wai 8 Manukau Harbour Report, which recognised the significant interests of Te Ākitai Waiohua in those lands and the surrounding areas. The Pukaki Urupā had fallen out of Maori ownership as it was sold while Te Ākitai Waiohua were in exile following the Land Wars. Today Pukaki Urupā is still landlocked and the only access is through private land which requires the permission of the legal owner.

The area surrounding Pukaki Marae comprises 7.6 acres of Māori freehold land owned by different whanau members of Te Ākitai Waiohua. This is all that remains of land returned under the Pukaki Compensation Court hearing.

Auckland Airport also had a severe impact on the local environment and access to kaimoana. Airport foreshore reclamations and operation restrictions on activities within the area limited the ability for any traditional fishing to occur around Pukaki and Ihumatao. These effects were exacerbated further by airport based pollution and runoff into the surrounding environs, including the Manukau Harbour and nearby Pukaki and Waokauri Creeks. A crash fire bridge was also built at the airport, but this new construction had the effect of impeding the flow of water from the Manukau Harbour into the Pukaki and Waokauri creeks causing increased siltation and affecting the local fisheries further. Both the Pukaki and Waokauri creeks were once navigable by boat in the 1850's, but this is no longer the case.

The introduction of a sewerage treatment plant in Ihumatao and four sewerage oxidation ponds between the Manukau Harbour shoreline and Puketutu Island (Te Motu a Hiaroa) in the 1950's is also an example of urban development impacting on Te Ākitai Waiohua. The main goal of this project was to meet the sewerage treatment needs of most if not all of Auckland.

This had obvious negative environmental effects in terms of unpleasant odours and midge infestations affecting the local residents of the area. However, it had a devastating impact on the water quality and flow of the Manukau harbour around Ihumatao, its local waterways including Oruarangi creek and the local fisheries with kaimoana that was rendered inedible. The sewerage works and oxidations ponds were built directly across oyster and scallop beds. These once important natural resources became practically unusable after the treatment plant development.

The concept of discharging waste into waterways in this manner, particularly where there is such a rich source of food, is an offensive breach of Te Ākitai Waiohua cultural values, illustrating that the project had little to no regard for Maori principles. To add insult to injury Ihumatao, including Makaurau marae, effectively sat next door to the oxidation ponds and treatment plant but were one of the last areas in Auckland to be linked to the sewerage treatment system. The treatment plant opened in 1960 and the residents of Ihumatao were finally connected in the late 1970’s. This development failed to benefit individual members of Te Ākitai Waiohua living in the Ihumatao area for nearly two decades.

The Manukau Harbour has been and is still affected by environmental concerns arising from multiple urban projects and local government infrastructure including stormwater, local farmland and piggery runoff, other forms of industrial waste and raw sewerage discharged into its waters through emergency overflow points around the harbour. Commercial fishing and various types of infrastructure running around, under and through the harbour have also impacted upon its integrity as a natural resource.

Local maunga (mountains) and volcanic cones have been lost either partially or entirely due to mining and quarrying developments. The Waitomokia, Maungataketake (Ellet's Mountain) and Matukutururu (Wiri Mountain) maunga have disappeared due to quarrying and most of the Puketutu cone on Te Motu a Hiaroa (Puketutu Island) has already been quarried away. Some places such as Te Tapuwae o Mataaoho (Sturges Park) have been heavily modified for modern development. These Manukau landmarks inhabited by ancestors of Te Ākitai Waiohua are mostly or completely gone now in the name of urban progress. The Otuataua stonefields in Ihumatao remain as one of the last enduring examples of Te Ākitai Waiohua occupation and history in the region.

Constant urban development in Auckland has not only impacted on the ability of Te Ākitai Waiohua to re-establish itself as an iwi, but it has affected the relationship of the iwi with its traditional environment. The ability for Te Ākitai Waiohua to meet its kaitiakitanga obligations and rangatiratanga aspirations are inextricably linked with the progress of Tamaki Makaurau.

TE ĀKITAI WAIOHUA TIMELINE

Pre-history - Te Ākitai Waiohua tupuna inhabit Tamaki Makaurau.

1000 – First radio carbon dating of occupation in New Zealand.

1100 – Portage at Otahuhu between Manukau Harbour and Tamaki River in use.

1200 – First radio carbon dating of occupation of Te Ākitai Waiohua sites at Matukutururu (Wiri Mountain) and Puhinui Estuary, Mangere.

1300 - Tainui canoe from Hawaiki travels up Te Wai o Taikehu (Tamaki River) to the Otahuhu portage and crosses to the Manukau Harbour and Te Motu a Hiaroa (Puketutu Island.)

1620–1690 - Huakaiwaka (Hua) forms Waiohua. He lived and died at Maungawhau (Mt Eden.)

1690–1720 - Ikamaupoho, son of Hua, leads Waiohua. He lived and died at Maungakiekie (One Tree Hill.)

1720–1750 - Kiwi Tamaki, grandson of Hua, son of Ikamaupoho and progenitor of Te Ākitai Waiohua, leads Waiohua at Maungakiekie before he is killed in battle.

1750–1754 - Waiohua lose a series of pa in Tamaki Makaurau and retreat to Drury, Pokeno, Kirikiri/Papakura and other parts of South Auckland. The last Waiohua pa in Tamaki is taken in 1755.

1760 - Waiohua tribes withdraw south from Tamaki to Papakura, Ramarama and surrounding areas.

1769 - Cook visits the Hauraki Gulf in the Endeavour. The canoe Kahumauroa is hollowed out by Ngāti Pou Waiohua and hauled across the portage to the Tamaki River where it is beached and finished.

Mid 1780’s – Te Ākitai Waiohua re-establish themselves at their traditional residences at Wiri, Pūkaki and Otahuhu.

1793 - Rangimatoru, son of Kiwi Tamaki, is killed in battle. He is succeeded by his son Pepene Te Tihi.

1821 - All volcanic cone pa of Tamaki Makaurau have been virtually abandoned as defensive fortresses with the introduction of the musket. War parties begin to raid the region and come into conflict with Te Ākitai Waiohua and other local iwi, which creates a period of great instability in Tamaki Makaurau.

1822-1825 - Te Ākitai Waiohua continue to stay in Tamaki.

1825 - The constant threat of forces armed with muskets eventually leads to Tamaki being abandoned.

1828-1835 - No one is attempting to reside in Tamaki.

1830-1835 - Te Ākitai Waiohua are based in Waikato under the protection of Chief Pootatau Te Wherowhero. They only return to parts of Tamaki for short periods of time.

1831 - Te Ākitai Waiohua including Pepene Te Tihi are observed by Charles Marshall at Pūkaki.

1835 - After nearly ten years in exile, Te Ākitai Waiohua return to Tamaki under the protection of Chief Pootatau Te Wherowhero, who makes peace with other iwi. Te Ākitai Waiohua re-establish themselves at Pukaki, Papakura, Red Hill and Pokeno.

1857-1858 – Kiingi Pootatau Te Wherowhero becomes the first Maori King. Te Ākitai Waiohua become a part of Kiingitanga or the Maori King Movement, which aims to unite Maori, authorise land sales, preserve Maori lore and deal with the Crown on more equal terms.

1861 - Ihaka Takaanini is chief of Te Ākitai Waiohua along with his father Pepene Te Tihi and they reside at Pukaki, Mangere and Ramarama (Red Hill near Papakura.) Ihaka is a significant landowner, land assessor for the Crown and keeper of the Maori hostels at Onehunga and Mechanics Bay.

1863-1864 – Before the invasion of Waikato in the time of the Land Wars, Ihaka is stripped of his roles and accused of being a Kiingitanga sympathiser and rebel. Tribal land at Mangere and Ihumatao is confiscated. Ihaka and twenty two whanau members, including three of his children, wife Riria and father Pepene Te Tihi are arrested at Ramarama and held without charge by the Crown at a military camp in Otahuhu. Pepene Te Tihi and two of Ihaka’s children die while in custody. Ihaka is moved to Rakino Island in the Hauraki Gulf and held there without charge or trial until his death in 1864. Ihaka is succeeded by his son Te Wirihana Takaanini, the only survivor of the three children originally held in custody.

1866-1969 – Although most of the land had been confiscated following the Land Wars and sold into private ownership, Te Ākitai Waiohua returned to Mangere and built a new marae in the 1890’s. The marae and associated community remained until the 1950’s when the pending construction of Auckland Airport in Mangere created zoning restrictions, forcing many Te Ākitai Waiohua members to move and live in other areas.

1970-Today – Te Ākitai Waiohua and the Waiohua tribes as mana whenua re-establish their ahi kaa in the central and southern areas of Tamaki Makaurau.

A new marae is built at Pukaki, Mangere and opened in 2004 by the Maori Queen Te Arikinui Te Ātairangikaahu.